Transdisciplinary wonders

Ecology is by definition an aggregation of life science disciplines, with tools regularly drawn from other disciplines such as mathematics, engineering or chemistry. When researchers integrate these other disciplines into their research framework, rather than just using their tools, the story becomes interdisciplinary!

At a time when funding agencies keep calling for more interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary in research by linking research to the stakeholders, we need to take a closer look at what this means for researchers and their work. What can we learn and gain from it? What are the main limitations and drawbacks?

In this project, we aim to describe and understand what transdisciplinary research means in practice by conducting a series of short interviews with researchers at the interface between ecology and other disciplines such as mathematics, physics, medicine, citizen science, social science, philosophy or politics.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Why should we bother to work interdisciplinary?

- What is the relevance of interpersonal relationships and communication?

- What importance do the products and recognition have?

- What is the best advice for a young scientist pursuing this path?

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐜𝐡

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

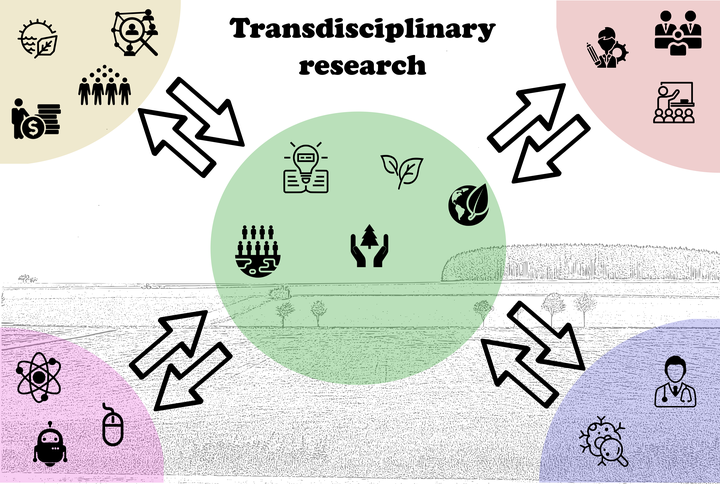

Over the next 14 days, we want to get to the bottom of transdisciplinary research. What transdisciplinary research is, why it is so relevant today, what are its obstacles. [1/22] pic.twitter.com/n9E4SCgeye

To answer the complex questions of ecology, a variety of tools drawn from other disciplines are often used. Now, when researchers integrate these other disciplines into their research framework instead of just applying their tools, the story becomes interdisciplinary. [2/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

The story becomes transdisciplinary when researchers begin to integrate non-academic collaborators into their research. [3/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

The story becomes transdisciplinary when researchers begin to integrate non-academic collaborators into their research. [3/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Collaboration between disciplines can take place at three levels of integration (definitions from Kelly et al. 2019 in Socio-Ecological Practice Research): multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary. [4/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Multidisciplinary research: “Different academic disciplines working together and drawing on their disciplinary knowledge in parallel, to conduct research on a single problem or theme but without integration.” (Kelly et al. 2019) [5/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Interdisciplinary research: “Different academic disciplines working together to integrate disciplinary knowledge and methods, to develop and meet shared research goals achieving a real synthesis of approaches.” (Kelly et al. 2019) [6/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Transdisciplinary research: “Different academic disciplines working together with non-academic collaborators to integrate knowledge and methods, to develop and meet shared research goals achieving a real synthesis of approaches.” (Kelly et al. 2019) [7/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

In practice, however, the boundaries between these three levels of cooperation remain blurred, and it is a continuum rather than a strict classification. [8/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

At a time when funding agencies are increasingly calling for transdisciplinary research, we need to take a closer look at what this means for researchers and their work. What can we learn and gain from it? What are the main constraints and drawbacks? [9/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

In this project, we aim to understand what transdisciplinary research means in practice. In pursuit of this goal, we conducted a series of short interviews with researchers at the interface between ecology and other disciplines, such as physics, medicine, politics, etc. [10/22]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Website: https://t.co/PSUCB8e7rr

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Twitter: @AlettaBonn pic.twitter.com/T0BvZC90YX

Website: https://t.co/u60LfdzBLT pic.twitter.com/8CXSHY6C3o

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Website: https://t.co/iJdwZMZLsL

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Twitter: @AndreaPerino1 pic.twitter.com/M5u93fc7PP

Website: https://t.co/OFa9qKiBFg [14/22] pic.twitter.com/89Rwt4njM5

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Website: https://t.co/D9OWmtbHCw

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Twitter: @stemcell1

[15/22] pic.twitter.com/5rxoaqaMac

Website: https://t.co/oOFpAiyuTv

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Twitter: @Rob_salgo

[16/22] pic.twitter.com/zXLJ3D3vis

Over the next fourteen days, we will explore the different aspects of multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary research by focusing on the following points:

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

[17/22]

14th: Why should we bother to work interdisciplinary?

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

16th: What is the relevance of interpersonal relationships and communication?

19th: What importance do the products and recognition have?

21st: What is the best advice for a young scientist pursuing this path?

23rd: Conclusion

We will compile all the tweets related to this project on our website after their publication: https://t.co/Fvk6ISrd7H

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

[19/22] pic.twitter.com/UIeHRMjbw9

Before we delve deeper into the subject, who are "we"?

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

[20/22]

I am Marie Sünnemann, PhD student exploring the impacts of climate change and land-use on soil communities in the @UFZ_GCEF and part of the Experimental Interaction Ecology group (@EisenhauerLab) at @iDiv.

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

Twitter: @Marie_Suen [21/22] pic.twitter.com/IQ8s3JUboV

I am Rémy Beugnon, a PhD student from the sino-german graduate school @TreeDi1, I am working in the Experimental Interaction Ecology (@EisenhauerLab) group at @iDiv.

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 12, 2021

More about me on my site: https://t.co/oFORugUgjo

Twitter: @BeugnonRemy

[22/22] pic.twitter.com/xcBSb3NZZT

2. Why should we bother to work interdisciplinary?

By definition, ecology is the study of “the relationships between the air, land, water, animals, plants, etc., usually of a particular area, or the scientific study of this” (Cambridge English Dictionary). [1/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Therefore, understanding ecosystems and how they function depends on our understanding of the subsystems of the ecosystem (i.e. air, land, water, animals, plants, etc.), but also on integrating all these subsystems into a holistic picture: the ecosystem. [2/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Humans are present everywhere and influence all ecosystems on earth ("Earth system science in the Anthropocene" by E. Ehlers & T. Kraff), therefore the study of an ecosystem must also consider the human subsystem and its dynamics in order to understand its full complexity. [3/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

A "perfect" example of this is the crisis of biodiversity in connection with the climate crisis, as summarised for us by Aletta Bonn: [4/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“The urgent questions of our biodiversity crisis, which is linked to the climate crisis and health issues, are wicked problems that cannot be solved by one discipline alone.” (Aletta Bonn) [5/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“Each discipline on their own can contribute to answers, but if we really want to solve some of the societally relevant questions, we need disciplines to come together.” (Aletta Bonn) [6/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

And when it comes to tangible actions, for example to protect ecosystems, society and its representatives must be integrated into the discussion. This is the crucial point at which interdisciplinary research becomes transdisciplinary. [7/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

This transdisciplinary approach and the connections between science and stakeholders are being pushed by public opinion nowadays. [8/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

There is a "need for politicians to back up their speech with strong evidence, such as scientific evidence, that helps them develop and back up their arguments" (Andrea Perino) [9/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Due to the "discussion about Fake News and Fake Science, policymakers have to work with references much more" (Andrea Perino). [10/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Furthermore, the need to answer holistic questions also drives us towards collaborations and inter- and transdisciplinary research. At the same time, these collaborations also offer huge opportunities for the disciplines themselves. [11/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Brent Reynolds, working with ecologists, was surprised to find that oncology and wildlife management have much more in common than one would expect: [12/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“Ecologists haven't been perfect at pest management, but they've done a much better job than the oncologist in being able to manage wildlife populations or manage pest populations.” (Brent Reynolds) [13/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“Virtually every single time I come to him [his ecologist collaborator] with some sort of problem we may be struggling with in the lab in our oncology experiments, he has a relevant example from the world of ecology.” (Brent Reynolds) [14/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Such examples show the high relevance of a level of knowledge that goes beyond specific disciplinary knowledge in order not to re-solve problems that are in fact already known elsewhere. [15/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Moreover, working outside one's own field also pushes the boundaries of that field. Martin Quaas gave us an example of this in relation to the economic management of fish populations. [16/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“A major step is to take the internal structure of the populations seriously, in particular with respect to age and size structure. It turned out to have important economic implications as well,” (Martin Quaas) [17/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“because one has a more differentiated perspective on the management of the fish populations. It does not only matter how many fish you take out but also what age group they are, that makes a difference.” (Martin Quaas) [18/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“Most scientists that I know are specialists in this tiny little area. They are incredibly knowledgeable, but sometimes having that broader view does make things seem simpler. It makes it easier to integrate other concepts from other fields.” (Brent Reynolds) [19/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

However, this openness also carries the risk that the concepts do not match. Cedric Gaucherel gave an example: thermodynamics theory has been developed by physicists for physical systems, reveals inappropriate for ecosystems.[20/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Even though thermodynamic concepts are easily transferable to biological systems at the level of the cell or organism, it becomes more difficult when it comes to ecosystems that contain living and nonliving components. [21/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

This unclear translation of concepts between domains can therefore lead to distortions or misappropriation of the concepts when they are used outside the system for which they were developed. [22/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Transdisciplinary research helps us to get a broader picture of the ecosystem, to solve disciplinary problems, it also proves to be essential to find the "relevant" ecological questions. [23/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“I've been talking to fishers and representatives of fishers organizations on a regular basis and continue to do that. It really helps to ask the right questions. The questions that are more fruitful and eventually more relevant.” (Martin Quaas) [24/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

At the same time, many of our interviewees consider transdisciplinarity their responsibility. [25/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“Taxpayers just want us to do something interesting and do something that's going to add value to the system. It's also part of our responsibility that we should be pushing those boundaries, even if pushing those boundaries is challenging for our individual careers.”(B. Reynolds)

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

This is in line with the larger mission of #scicomm: "We have a duty to communicate and address our pressing problems. They link across sectors and disciplines, and they will not be solved by a single discipline." (Andrea Perino) [27/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

However, the involvement with politics and public discussion comes with risks, as Andrea Perino explained to us.[28/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“Our job as scientists is not pushing a certain political agenda but, but to provide the information, and then people can do what they feel is right with that information.” (Andrea Perino) [29/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“[...] we should not be the one to say: you should do this, you should do that, because that is the job of politicians and decision-makers.This is called a knowledge broker approach. " (Andrea Perino) [30/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

"In our field, everyone is emotionally involved". We must nevertheless "try to bring the facts as unmistakably as possible." (Andrea Perino) [31/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

In summary, transdisciplinary research offers the opportunity to advance individual disciplines by bringing concepts and methods together to tackle challenges with a holistic approach. [32/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Acknowledging the relevance of transdisciplinary research, we wondered how these projects are initiated and built? You need a fundamental common interest. [33/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

And that requires a "huge curiosity" that drives you every day to read new things in order to understand the object you are working with. “Our enthusiasm is far enough to bridge the gap.” (Cédric Gaucherel) [34/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Rob Salguero-Gómez, for example, told us how his collaboration with the Oxford robotics department started. [35/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

When he arrived at Oxford College, he gave a talk about his work and his perspective, highlighting the problem of collecting data in the field: sampling errors, time-consuming, expensive, etc. [36/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Afterward, a robotics engineer sought him out: "Hey Rob, it seems like you have a lot of challenges that you need to overcome. In my group, we look for challenges and develop solutions", thus it was a "perfect marriage" (Rob Salguero-Gómez). [37/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

What surprised us in our respondents' answers was the strong correlation between successful projects and successful relationships, often resembling friendships. [38/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

“I choose collaborators that I look up to scientifically and I look forward to drinking a good glass of wine with on a friendly perspective” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [39/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

You need to find a good set of people, “identifying the appropriated people you want to work with, bright and motivated, kind and caring.” (Cédric Gaucherel) [40/40]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

Ultimately, "interdisciplinarity is not that you always sit together, but that you have phases of intensive interdisciplinarity. Then you go into your own discipline and come together again." (Aletta Bonn) [Final]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 14, 2021

3. What is the relevance of interpersonal relationships and communication?

Our previous thread showed that successful collaboration is crucial in transdisciplinary projects. This is mainly explained by the impossibility of being an expert on all subjects. [1/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“I'm convinced that interdisciplinary work is most properly done by more than one person when different people from different disciplinary backgrounds come together. It does not make a lot of sense to just work interdisciplinary alone.” (Martin Quaas) [2/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Here, of course, one thing above all is important: communication. Therefore, it is essential to create a common basis right from the start: [3/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“I spend a lot of time being able to really understand what's going on in the other discipline, to have solid ground to move forward. If everyone doesn't have the time or willingness to spend that effort, then it can go seriously wrong.” (Martin Quaas) [4/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“Actually putting those brains together to interact and learning from each other with a common language for communication comes before you develop the ideas: you first need to communicate.” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [5/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

This is true for all projects, but again, it is critical for transdisciplinary work to have the courage to ask: "Wait, stop, explain to me the meaning behind this term” (Cédric Gaucherel) [6/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

This becomes challenging with transdisciplinary projects, “you start intermixing ideas, particularly to another field where people have not been trained to accept those new ideas.” (Brent Reynolds) [7/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“The beginning is very difficult, but then there is a step where you shift your mind, you start to adapt, [...] I will never think as a sociologist, but I am starting to understand them.” (Cédric Gaucherel) [8/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Finally, the method to do this is quite simple, “be curious” (Cédric Gaucherel) and “listen, first of all, try to understand, try to also be humble. Read some papers, ask about their concepts.” (Aletta Bonn) [9/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“For me it would also be taking somebody outside and showing them my knowledge of biodiversity, with that you really have an in-depth exchange afterwards.” (Aletta Bonn) [10/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“You have to be responsible to a large extent for what the other disciplines do, [...] so I wouldn't necessarily collaborate with somebody from quantum physics just for the sake of it, if I didn't quite understand a little bit about that area.” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [11/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Such quotes illustrate the balance one has to find between trust and knowledge. You can't know everything, but you can't completely ignore the other field when you work with it. [12/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“You don't necessarily always need to understand everything about the other disciplines to collaborate, but obviously there is a trust and recognition of the other theories and methods.” (Aletta Bonn) [13/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“For the analysis, for the more developed aspects of it, you work with someone who really understands their craft and their art, so you have to rely on them a little bit, but then through frequent conversations." (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [14/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Once this first step is done, you can start talking about science: [15/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“In a science project, you start with sometimes fuzzy ideas and then develop more concrete questions. A hypothesis that you can test, which suits both disciplines or more than one discipline. You have to come from different angles.” (Aletta Bonn) [16/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“The idea and project have to be concrete and focused. If you cannot focus and come to a clear design and a clear study, then it's just going to be a nice conversation, but it doesn't harbor anything more.” (Aletta Bonn) [17/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“To then whittle it down to one question, you may have to make some concessions and then it can become something really beautiful.” (Aletta Bonn) [18/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Such concessions could arise from strong cultural differences between the disciplines: [19/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“My experience is that scientists are open to new perspectives and new ideas, but of course it may be a little bit more difficult to explain what one is doing to an audience that is not familiar with those approaches.” (Martin Quaas) [20/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Also, disrespect between disciplines “ is a really easy way to kill a potentially fruitful collaboration.” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [21/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“You want to push your own boundaries to get comfortable outside your own zone, but equally you respect that you will not know everything. That's why we're working together with other people and value this teamwork.” (Aletta Bonn) [22/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“The successes and failures are not dependent on the discipline rather than in people's willingness.” (Cédric Gaucherel) [23/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Cultural differences may come from the tools that are different between disciplines. There is a steep learning curve to reach other tools, but they are “transgressive so you can apply them from one field to the other.” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [24/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

The difficulty may be deeper down in the method. “It may be easier for us ecologists to listen to mathematicians, just because we are closer to their method framework as ecologists. It may be easier than the interaction with philosophers who frame things differently.” (A. Bonn)

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

“It may be easier for ecologists to work with quantitative scientists. Qualitative approaches can be as interesting and as valid, while it may take more time to get used to and understand each other, and also to trust each other.” (Aletta Bonn) [26/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

Taken together, communication is the key between the different parts. [27/27]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 16, 2021

4. What importance do the products and recognition have?

Goring et al. (2014) warned us about the mismatch between transdisciplinary outputs and the way scholarly outputs are valued by the community. [1/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

In this thread, we will explore the possible outputs that we face and the matches and mismatches with scientific careers. [2/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

(Goring et al. 2014 Improving the culture of interdisciplinary collaboration in ecology by expanding measures of success in Macrosystems ecology) [3/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

Scientists are judged on their ability to produce high-impact scientific papers. Is the scientific world ready, after all, for the complex outputs of interdisciplinary projects? [4/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

The first challenge arises from the field-specific organisation of journals and the rarity of transdisciplinary journals. [5/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

Brent Reynold can testify that “it has been sort of a battle again from the world that I live in [oncology] to get people to accept that idea [of interdisciplinary relation with Ecology].” [6/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“It doesn’t matter what field you're in, people do not like new ideas. We get trained in a certain way, and anything that goes against that training must just be sort of a wacky type thing.” (Brent Reynold) [7/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

For Rob Salguero-Gómez, “it's a bit more tricky to work with [transdisciplinary papers] as an editor. Usually, you identify the main disciplines that have come together in that paper. It's a challenge if you don't understand the landscape of the different disciplines.” [8/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

In addition, “one challenge is that the different disciplines have different habits with respect to publications and co-authorships. In economics, the standard used to be to have single-authored papers, sometimes two authors.” (Martin Quaas) [9/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“The challenge is also to organize the authors internally. From a human perspective, to make them feel appreciated, because every one of them is a crucial piece of the puzzle, otherwise, they wouldn't be working on a specific product.” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [10/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“So why not do two publications, one where the biologist is first author and one where the economist is first also and then highlighting the aspects that are relevant for the respective discipline and then you have two publications.” (Martin Quaas) [11/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

Goring et al. emphasize that transdisciplinary work is full of other major and minor products such as databases, scholarly communication outputs, artworks, policy briefs. The impact of these products can be difficult to quantify. [12/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

For example here, what will be our impact with this thread? (please tell us!) [13/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“Sometimes, you see your idea picked up somewhere, but there's no way to tell if it's yours, it is hard to track and to assess in a very structured way.” (Andrea Perino) [14/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

In art projects, “the artists had a totally different approach to biodiversity and it was fascinating. I cannot judge what is good art. But as long as it is fun to me, and if it broadens my own vision, it doesn't have to go into a paper” (Aletta Bonn) [15/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

We get to an important point here: some achievements are not career-related and do not have to be. [16/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“Scientific ideas and scientific career [evaluations of scientists] doesn’t necessarily follow the same path.” (Cédric Gaucherel) [17/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

Such differences between scientific ideas and scientific recognition through publication may have direct consequences for the scientist's career, starting with funding opportunities. [18/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“You often need to shift your paper/grant writing to follow expectations and hide the transdisciplinary part.” (Cédric Gaucherel) [19/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“If you want to be successful with a grant proposal, you often still have to position yourself firmly in one discipline.” (Aletta Bonn) [20/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

This is mainly due to the structure of the funding system. Projects have to be applied for in certain disciplines, which is why it is expected that this discipline will be predominant. There are not many funding systems that allow more flexibility. [21/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

The promotion of transdisciplinary research should therefore ultimately not only take place on the personal, individual level. Major changes on a structural level are also needed here. [22/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

“As an organization, @iDiv we should work towards this transdisciplinary research systematically. It should not be just on the individual to push these boundaries.” (Aletta Bonn) [23/23]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 19, 2021

5. What is the best advice for a young scientist pursuing this path?

Transdisciplinary projects are long-term projects, with possible uncertainty of funding and publications. Does it make sense at all for a young researcher to go down the path of transdisciplinary research? [1/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

This was our last question to our interviewees: "What advice would you give to a young researcher who wants to engage in transdisciplinary research? How would you support her/him as PI? [2/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

The first problem the young researchers encounter is the time frame of their contracts: “It takes at least a couple of years to do interdisciplinary research, this is why it's difficult to do serious interdisciplinary research during a PhD.” (Martin Quaas) [3/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

You must first be established in your own discipline. [4/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

“If I was an advisor to a PhD student or early careers scientists, I would advise them to develop strong skill sets first - these can then be applied also in interdisciplinary settings.” (Aletta Bonn) [5/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

“First, become an expert in your field first. Second, building interdisciplinary narratives by emailing people, having chats, meeting with people at conferences.” (Rob Salguero-Gómez) [6/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

“I do not encourage early career researchers to do interdisciplinary research, but sometimes they are interested in problems that require interdisciplinarity.” (Martin Quaas) [7/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

“The best advice I have for PhD students and postdocs is to just follow your passion, follow your ideas. That idea of security doesn't exist in our world, we create this false sense of security for ourselves.” (Brent Reynolds) [8/8]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 21, 2021

6. Conclusion

Today, our world and society are challenged by various crises, such as socio-economic, climatic, or biodiversity crises. These crises occur simultaneously and are interconnected. [1/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

However, these problems are usually studied independently by the experts of the respective disciplines. [2/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

But only by putting the puzzle of the different disciplines together in inter- and transdisciplinary projects can we pursue the big picture and strive for solutions for our society, the climate, and biodiversity. [3/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

With our project, we wanted to explore the question of how young scientists can address these complex transdisciplinary questions. Here we have focused on learning from researchers who have experience in dealing with this issue. [4/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

We learn that transdisciplinary projects are facing the same issues as any project: the need for clear communication between the parties. [5/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

As communication is one of the most important tools for disciplinary scientific projects and can be a constraint, it is also a critical factor for transdisciplinary projects. [6/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

This is the result of the merging of different worlds with different expectations, methods, and vocabulary. [7/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

Therefore, the success of transdisciplinary projects may depend more on the relationship between the collaborators than on academic performance. [8/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

It might therefore be advisable when looking for collaborators to seek not only scientists but also people with whom one would like to have a glass of wine. [9/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

But the academic system does not necessarily prepare an easy path for young scientists. [10/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

Both the duration of transdisciplinary projects and the discrepancy between transdisciplinary outcomes and academic demands do not fit the requirements of an academic career. [11/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

It may therefore be advisable to delve deeply into the chosen topic during the doctoral thesis in order to become an expert in one's own discipline. [12/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

In order to subsequently enrich inter- and transdisciplinary projects with this knowledge. [13/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

But there is one thing you can do beforehand: talk to interesting people, ask them what comes to your mind, what you always wanted to know but never dared to ask. [14/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

Because it was the in-depth conversations (even if we could only have them via Zoom) that made us look into new, unknown worlds with fascination. And that is what inspired us the most. [15/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

With these words, we close our thread on the wonders of transdisciplinary research. [16/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

Please let us know what you thought about it. [17/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

Please tell us about your own inter- and transdisciplinary experiences. [18/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

We would like to thank all our interview partners: @AlettaBonn, Cédric Gaucherel, @AndreaPerino1, Martin Quass, @stemcell1, @Rob_SalGo. [19/19]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021

And we would like to thank @GfoeSoc for this opportunity.@Marie_Suen & @BeugnonRemy [THE END]

— GfÖ (@GfoeSoc) April 23, 2021